I don’t have a lot to show this time around, but what I do have is a pretty useful trick. The bottom shelf of my endtable presents an interesting problem, because it’s made from solid wood. I wanted the shelf to completely fill the space between the aprons. That’s easier than it sounds when you take into account how much a panel that wide will move. A dado in the aprons got me part way, but I floundered for a while with how to best handle the shelf/leg intersection. I really didn’t want to chop out a square slot in all 8 legs.

I went to visit my parents last weekend, and while helping my dad install some new fence posts he explained a trick he learned a while back. It took a little while for me to grasp, as it seems counter intuitive. Basically all you need to do is make a dado across the corner of the legs, and then chamfer the corners of the shelf. Hopefully the following pictures will explain it better.

Continue Reading…

It took an entire week, but all 32 mortise & tenons have been fitted. If I learned nothing else from this project, it’s that floating tenons are the way to go when you are using hard exotics. Rounding over the ends of the Jatoba tenons was not a fun process. In softer woods it’s a breeze with a file and a chisel, but in Jatoba the file would skip a lot, and cleaning up the shoulder end-grain required a mallet. Unlike softer woods Jatoba has no give, so if a tenon was off a little in thickness it had to be fine tuned by hand. I enjoyed the process, but needless to say next time I’m going to use a faster joinery method.

Welcome to pattern routing 220, This semester we will be covering advance techniques. All joking aside, I did use some more advanced, and less intuitive techniques to shape the bottom aprons of the end tables that some might find interesting. In an earlier post I posted the photo bellow of a template that I made to rout the bottom aprons but didn’t really talk about it. Now that I’m to the pattern routing phase, it’s time to spill the beans. As you can see in the photo below the template has 3 bounding blocks. Bounding blocks are needed to positively locate the apron, because aprons must be routed in two faces.

apron template

The first step is flush the apron to the template. In my opinion, with a wood as hard and chip-out prone as Jatoba, The best type of router bit to use is a spiral compression bit. Compression bit’s are specifically designed to prevent chip-out. They are pretty expensive, The one I have cost over $100, but it’s become my go to bit for all pattern routing jobs. The apron is secured to template with another workhorse in my shop, turners tape. As you can see in the following photo, the profile curve extends well past the ends of the apron. It might not seem that significant, but it allows the bit to be positively registered against template before it’s feed into the workpiece. This helps prevent kickback, & also yields a smother cut.

pattern routed

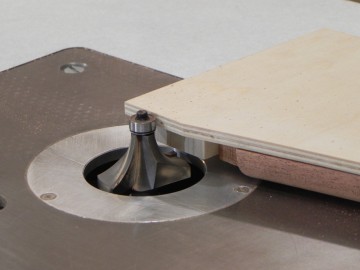

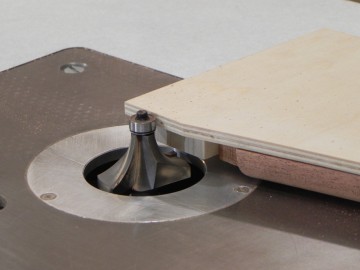

The second step is to round over the bottom outside edge of the apron. Again the template plays a key part in this step. Since the round over had a 3/4″ radius and the stock is only 25/32″ thick, routing the profile is literally impossible without the template for the bearing to ride on. Just like in the previous step, since the template extends past the end of the apron the bit can be feed into the cute without fear of kickback. Additionally, you don’t have to worry the bit going around the end of the apron, and messing up all your hard work.

It’s been two weeks since my last post, but I actually have a good reason for not posting sooner. If you have ever made mortise and Tenon joints, you know they can be hard to get perfect using power tools. The most common tool used to make tenons is the table saw. You cut your boards to length set up a stop block, and then guide the board through the cut using a miter gauge. This method has a draw back though, your miter gauge must be perfectly square to the miter slot, and it can have now slop as it travels through the slot. If your set-up doesn’t meet both these requirements the checks won’t end up in the same plane, and thus one side of your joint will have a gap. If the gap is small then it’s usually not a big issues, because very rarely are both sides of a M&T joint visible. Continue Reading…

So it took almost a 5 days for my back to start feeling better, So I didn’t get as much done as I wanted.

While my back was still tender I made the two pattern routing templates need for the bottom aprons, as they are one of the things you can make while sitting on a comfortable stool. I’ve started making all my templates from 1/4″ Baltic Birch, as it holds up so much better than MDF, and is a lot less messy to use. It took about 4 hours to make both of them, and most of that was fine-tuning the shape with sanding sticks. This YouTube video explains the technique better than I can.

apron template

When my back was finally better, I started the loud and time consuming process of sizing all the stock for the aprons. I’m not exaggerating, jointing and planing Jatoba trashes most knives. My planer is probably 10 decibels louder than when I started. It took several days, because I had to buy 5/4 stock and then take it all the way down to 25/32″. Removing this much stock required 3 rounds of jointing and planing separated by 24 hour rest periods. My rule of thumb, is a 24 hour rest period for every 1/8″ of stock removed.

sized aprons

One of the things I’m trying for the first time on this project, is a continuous drawer front. If you’re not familiar with technique, you start out by taking stock wider than the final final apron and sawing it into 3 pieces lengthwise. The top and bottom pieces are narrow, and th e middle piece is as wide as your drawer is high. After you joint the freshly cut faces, you cut the drawer front out of the center piece. The final step is to glue the top and bottom pieces to the ends of the center piece, and then plane the glue up to final thickness. This Charles Neil YouTube video shows the process step by step.

drawer front